Today’s guest tutorial comes to you courtesy of X.

TODO!

Circumcircle (B)

Now that we know about the radical axis, we can turn some of its ideas around.

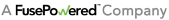

Given two points with such an axis, a line will run perpendicular to its middle. Somewhere along that line will be the center of a circle, depending on the shape of the arc.

As this very variety demonstrates, two points alone are unable to pin the center down.

As one choice of center, could be the one that would see the other point also on the circle.

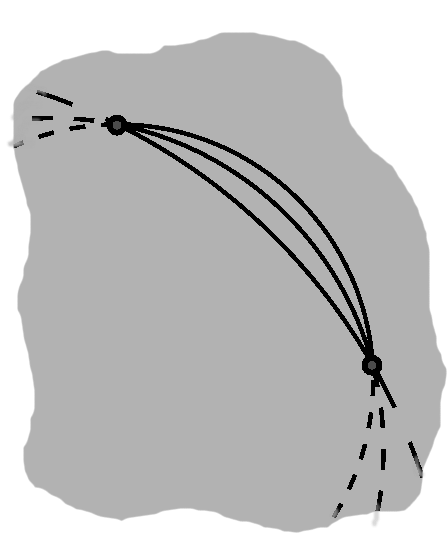

If we had a circle, we could put another point on it somewhere. There would then be two new arcs between this and the original two points. These will naturally have their own radical axes and corresponding perpendicular bisectors.

As the figure suggests, this immediately constraints a center. (In fact, two arcs are enough to do so, on the unit circle.) For that matter, the bisectors all intersect there.

(TODO: there is good material in these last three, but needs some consistency)

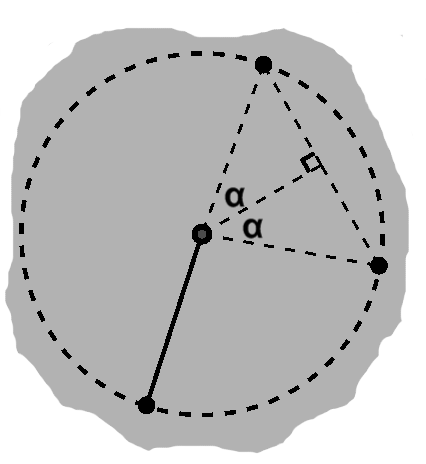

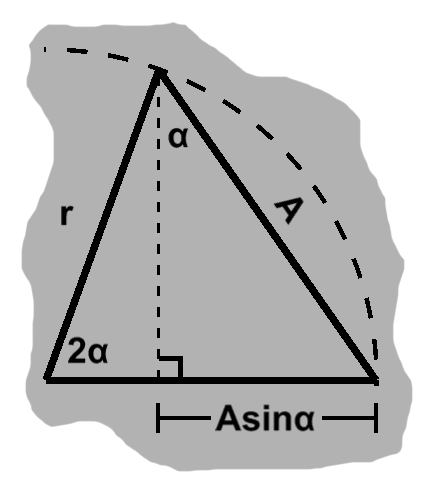

We have a trio of bisected radial isosceles triangles. These will have outer sides of $ 2r \sin\alpha, 2r \sin\beta, $ and $ 2r \sin\gamma $ with those half-angles, respectively.

Now, presumably we know what these three points are. So we can use our length formula to give concrete values to these lengths. Call the above $ A, B, $ and $C. $

We saw earlier how to break down the structure of a double-angle triangle. So we can express the radius as $ r = r\cos 2\alpha + A\sin\alpha. $ But we know that $ \frac{A}{2r} = \sin\alpha. $ After substitution and some rearrangement, this becomes $ \cos 2\alpha = 1 - \frac{A^2}{2r^2}. $

(TODO: We CAN just pull this from the formula, but might provide more insight)

We can apply this same analysis to the other two triangles.

At this point, it will be helpful to presume we already have our circle and are on it. Thus we want to deal with some local points. For instance, $ \vcomps{x_1}{y_1}, $ where $ x_1 = p_x - c_x $ and $ y_1 = p_y - c_y, $ and likewise for $ \mathbf{q} $ and $ \mathbf{r}. $

From the figure, we can see that these points are simply rotations of one another. So we can express them as such: $ x_2 = x_1\cos 2\alpha - y_1\sin 2\alpha $ and $ y_2 = x_1\sin 2\alpha + y_1\cos 2\alpha. $

We can use the same strategy from angle differences to simplify this and then add the equations together. Doing so, we wind up with $ x_1 x_2 + y_1 y_2 = (x_1^2 + y_1^2) \cos 2\alpha. $

Points on the circle will of course hold to $ x^2 + y^2 = r^2, $ so this simplifies, after using the earlier result for $ \cos 2\alpha, $ to $ x_1 x_2 + y_1 y_2 = r^2 - \frac{A^2}{2}. $

The very same strategy will give us $ x_2 x_3 + y_2 y_3 = r^2 - \frac{B^2}{2}. $

We can combine these equations by subtracting one from the other, giving us $ x_2(x_3 - x_1) + y_2(y_3 - y_1) = \frac{A^2 - B^2}{2}. $

At this point, we can start reinflating our center-relative coordinates. Within the first parentheses, we have $ r_x - c_x - p_x + c_x, $ and likewise within the second set. We soon get $ (q_x - c_x)(r_x - p_x) + (q_y - c_y)(r_y - p_y) = \frac{A^2 - B^2}{2}. $

Now, everything but $c_x$ and $c_y$ here are constants. We can reduce the clutter a bit by grouping them, say as $ D = -(r_x - p_x), E = -(r_y - p_y), $ and $ F = q_x D + q_y E + \frac{A^2 - B^2}{2}. $ This will give us $ Dc_x + Ec_y = F, $ the equation of a line of potential centers.

At this point, we are still at the impasse we were in before. We need to impose more constraints on the line.

We still have the relationship between $ \mathbf{r} $ and $ \mathbf{p} $ to exploit. As before, we will come up with $ x_1 x_3 + y_1 y_3 = r^2 - \frac{C^2}{2}. $ We can combine this as before with either of the other equations to bring in $ \mathbf{q} $, for instance as $ x_1(x_3 - x_2) + y_1(y_3 - y_2) = \frac{A^2 - C^2}{2}. $ This will give us another line as $ Gc_x + Hc_y = I. $

We can arrange this to put $c_y$ totally in terms of $c_x,$ for instance $ c_y = \frac{F - Dc_x}{E}. $ We can then feed it into the second equation, for $ Gc_x + \frac{H(F - Dc_x)}{E} = I, $ or $ \left(G - \frac{HD}{E} \right)c_x = I - \frac{HF}{E}. $ Multiplying by $E$ and rearranging, this is $ c_x = \frac{EI - HF}{EG - HD}. $

(TODO: EG - HD = 0)

Now that we have $c_x,$ we can feed it back in to get the equation for $c_y.$ In the event that $E$ is 0, we can use the second line equation to get it.

Now that we have actual values for the center, we can lock down our earlier center-relative points, say $x_1$ and $x_2.$ Thus, we can choose one of them arbitrarily and solve $ r = \sqrt{(p_x - c_x)^2 + (p_y - c_y)^2}. $ (No need to take negative roots.)

This process might sound a bit daunting, but it boils down to some fairly tight code:

local sqrt = math.sqrt

function Circumcircle ( px, py, qx, qy, rx, ry )

-- Squared side lengths.

local A2 = (qx - px)^2 + (qy - py)^2

local B2 = (rx - qx)^2 + (ry - qy)^2

local C2 = (px - rx)^2 + (py - ry)^2

-- Center lines.

local D, E = px - rx, py - ry

local F = qx * D + qy * E + (A2 - B2) / 2

local G, H = qx - rx, qy - ry

local I = px * G + py * H + (A2 - C2) / 2

-- Solve for the circumcenter.

local cx, cy = (E * I - H * F) / (E * G - H * D)

if E^2 < 1e-12 then -- choose from non-vertical line of centers

cy = (I - G * cx) / H

else

cy = (F - D * cx) / E

end

-- Solve for the circumradius.

return cx, cy, sqrt( (px - cx)^2 + (py - cy)^2 )

endFrequently it will be the case that a lot of work leads to a nice formula. With some of the ideas in the next article we can make this even more concise.

EXERCISES

1. Find trilinear coordinates for the circumcenter.

2. Find the circumcircles of both a triangle and its orthic triangle. What can we say about the radii of these two circles?

The inner circle... (C)

We might also try to find a circle inside a triangle.

Presumably we would only want it to touch the sides, which would mean these are tangent to the circle at those points. Thus each segment from the center is perpendicular to the side.

These segments will all have radial length, of course. So we may slice out an isosceles triangle thus. Doing so will also carve out a second triangle.

This triangle has angles complementary to those of the first. Thus, it also happens to be an isosceles.

Thus, between these two side points we have a radical axis.

Now, we can split this triangle in half and concentrate on a right triangle. Its hypotenuse is the distance of the side point from $ \mathbf{q}. $ We can call this $ A' $ with $A$ itself as the distance from $ \mathbf{p} $ to $ \mathbf{q}. $ Then $ A - A' $ is the other length.

This situation prevails on each side, so we find lengths $ B, B', C, $ and $C'$ as well.

Now, because of the isosceles, we have $ A' = B - B'. $ Likewise, $ B' = C - C' $ and $ C' = A - A'. $

By substitution, $ A' = B - (C - C') $ and further $ A' = B - (C - (A - A')), $ or $ 2A' = A + B - C. $ Finally, $ A' = \frac{A + B - C}{2}. $ Plugging this back in, we get $ B' = \frac{B + C - A}{2} $ and $ C' = \frac{A + C - B}{2}. $

The first side point is $ A' \over A $ of the way from $ \mathbf{q} $ back to $ \mathbf{p}. $ Similarly, we can interpolate the other points.

At this point, we have three points with an implicit underlying triangle exhibiting the arc behavior from before, so it would actually suffice to find their circumcircle. Nevertheless, it is worth using the situation at hand.

Returning to the right triangle, let us find its leg lengths. The triangle's corners consist of one side point, its midpoint with another, and $ \mathbf{q}. $ We can easily take their lengths, giving us $ A'\cos\beta = \sqrt{(m_x - x_1)^2 + (m_y - y_1)^2} $ and $ A'\sin\beta = \sqrt{(q_x - m_x)^2 + (q_y - m_y)^2}. $ For clarity, call these roots $H$ and $V$ for horizontal and vertical, respectively.

Now, we know $ \alpha + \beta = 90^{\circ}. $ This lets us put those in the other slots in the larger right triangle and tells us that $ r = A'\tan\alpha. $

From the geometry we see that $ \cos\alpha = \sin\beta $ and $ \sin\alpha = \cos\beta, $ thus $ \tan\alpha = \frac{H / A'}{V / A'}, $ and $ r = A'\frac{H}{V}. $

To find the center, we want to follow $ \mathbf{q} $ to the midpoint $ \mathbf{m}, $ then push on a little farther.

That longer distance is the hypotenuse of the right triangle, so it has length $ r\sec\beta. $ We see elsewhere that $ A' = H\sec\beta. $ After adding our above result for $r,$ the length is $ \frac{(A')^2}{V}. $ We want its ratio to $V,$ of course, so the final scale factor is $ \left(\frac{A'}{V}\right)^2. $

Our center quickly follows from this. Again in code:

local sqrt = math.sqrt

function Incircle ( px, py, qx, qy, rx, ry, want_contact_triangle )

-- Side lengths.

local A = sqrt( (qx - px)^2 + (qy - py)^2 )

local B = sqrt( (rx - qx)^2 + (ry - qy)^2 )

local C = sqrt( (px - rx)^2 + (py - ry)^2 )

-- Partial side lengths.

local Ap = (A + B - C) / 2

local Bp = (B + C - A) / 2

-- Find a couple contact points.

local a1, b1 = Ap / A, Bp / B

local a2, b2 = 1 - a1, 1 - b1

local x1, y1 = a1 * px + a2 * qx, a1 * py + a2 * qy

local x2, y2 = b1 * qx + b2 * rx, b1 * qy + b2 * ry

-- Get the midpoint between them. The midpoint is along the way from the corner shared

-- by the two sides, i.e. q, to the center. Evaluate this partial route.

local mx, my = (x1 + x2) / 2, (y1 + y2) / 2

local hx, hy = mx - x1, my - y1

local vx, vy = mx - qx, my - qy

-- Together, one of the contact points, the midpoint, and q describe a right triangle.

-- Get its leg lengths, the "horizontal" and "vertical" distances.

local H2, V2 = hx^2 + hy^2, vx^2 + vy^2

-- Find the radius.

local scale = Ap^2 / V2 -- q-to-center : q-to-midpoint = r * sec(beta) / V = (A' / V)^2

local r = sqrt(H2 * scale) -- r = A' * tan(alpha)

-- Scale the direction found earlier. Walk along it from q to reach the center.

local cx, cy = qx + scale * vx, qy + scale * vy

-- If requested, find the third, otherwise-redundant contact point and supply the triangle.

if want_contact_triangle then

local Cp = (A + C - B) / 2

local c1 = Cp / C

local c2 = 1 - c1

local x3, y3 = c1 * rx + c2 * px, c1 * ry + c2 * py

return cx, cy, r, {

a = { x = x1, y = y1 }, b = { x = x2, y = y2 }, c = { x = x3, y = y3 }

}

end

return cx, cy, r

endEXERCISES

1. What are the incenter's trilinear coordinates?.

...and the fringe (D)

By relaxing our constraints a little, it turns out there are more circles that touch all three sides of a triangle.

The key is that two of these will be extensions of the triangle's sides, so-called sidelines.

Then we have one touch on a true side, two more on these extensions. This is true for each of the triangle's three sides, giving us the excircles.

As with the incircle, we begin with the insight that we have radius-length segments emanating from a center, with the circles themselves tangent to the sides.

As can be seen, this will give us a couple adjacent sectors on the circle, grazing the side in question.

Since these are radius-length, part of each sector will be an isosceles triangle. As with incircles, since the common angles were each part of a right angle, the complementary angles also give a second isosceles.

Thus we get the fairly familiar quadrilateral, which we can exploit.

First, since the two angles are the same, we know the remaining one is supplementary to their sum. This in turn tells us that the adjacent angle is valued at their sum.

Importantly, we can go "right" by $ (B - B')\cos 2\alpha, $ then "up" by $ (B - B')\sin 2\alpha, $ to arrive at one of the contact points.

Second, via a combination of the complementarity of the angle and the fact that the midpoint in the quadrilateral occurs at a right angle, we know the angle bubbles up top.

In other words, we have $ r\tan\alpha = B - B'.$ We would get something similar on the left: $ r\tan\beta = B'.$ If we add these together, we have $ r(\tan\alpha + \tan\beta) = B, $ or $ r = \frac{B}{\tan\alpha + \tan\beta}. $

These results apply to both sectors, of course.

Up to this point, we have ignored our triangle's third point, but now can bring it back into play.

In particular, we have a vertical angle with the previous supplementary angle.

We already saw how to find this foot, where all the points are available, above with the orthocenter. This will split up the side into two parts, $L$ and $R.$ Note that this foot generally differs from that of the excircle center, as in this example.

We can now start plugging in hard numbers.

We know this angle on the right is $ 2\alpha, $ so we have $ \cos 2\alpha = \frac{R}{C}, $ $ \sin 2\alpha = \frac{h}{C}, $ and $ \tan 2\alpha = \frac{h}{R}. $

Now, $ \tan 2\alpha = \frac{2 \tan\alpha}{1 - \tan^2\alpha}. $ We can find the squared term as $ \frac{1 - \cos 2\alpha}{1 + \cos 2\alpha}, $ which with some substitution is $ \frac{C - R}{C}\frac{C}{C + R}. $ Simplifying and subtracting from 1, we end up with $ 2\frac{R}{C + R} $ in the denominator.

We already have our result for $ \tan 2\alpha, $ so we can plug that back in and rearrange everything in terms of $ \tan\alpha. $ In the end we have $ \tan\alpha = \frac{h}{C + R}. $ Finding $ \tan\beta $ proceeds similarly, albeit with $A$ and $L.$

With these, $r$ follows immediately, then $B',$ giving us our middle foot.

From there we can scale the middle segment and go up to find the remaining contact points.

(NOTES: ROUGH! Need to find best way to work in all the angles and points... but already better)

In code, it will go something like:

local sqrt = math.sqrt

local function DoExcircle ( px, py, qx, qy, rx, ry, circles, contacts, extouch, side )

-- Deltas for sides A, B, C.

local ax, ay = qx - px, qy - py

local bx, by = rx - px, ry - py

local cx, cy = qx - rx, qy - ry

-- Squared side lengths.

local A2 = ax^2 + ay^2

local B2 = bx^2 + by^2

local C2 = cx^2 + cy^2

-- Using the orthocenter approach, find the offset of the foot of q on segment pr, as

-- well as the height of the associated altitude.

local bt = .5 * (A2 + B2 - C2) / B2

local h = sqrt( A2 - B2 * bt^2 )

-- Side lengths.

local A = sqrt( A2 )

local B = sqrt( B2 )

local C = sqrt( C2 )

-- Break the pqr triangle into two right triangles at the foot and use this to find angle

-- information shared by the excircle. This will give us the radius.

local L, R = bt * B, (1 - bt) * B

local TanA, TanB = h / (C + R), h / (A + L)

local kr = 1 / (TanA + TanB)

-- From the radius we can find the foot of the center onto the triangle side. Reaching the

-- center is then simply a matter of walking up the altitude.

local Bp = kr * TanB

local Fx, Fy = px + Bp * bx, py + Bp * by

-- Given the foot and radius, similar triangles will put us at the center.

circles[side] = { x = Fx - kr * by, y = Fy + kr * bx, r = B * kr }

-- If requested, supply the contact triangle and / or one side of the extouch triangle.

if contacts or extouch then

Bp = Bp * B

local at, ct = Bp / A, (B - Bp) / C

if contacts then

contacts[side] = {

a = { x = px - at * ax, y = py - at * ay },

b = { x = Fx, y = Fy },

c = { x = rx - ct * cx, y = ry - ct * cy }

}

end

if extouch then

extouch[side] = { x = Fx, y = Fy }

end

end

end

function Excircles ( px, py, qx, qy, rx, ry, want_contact_triangles, want_extouch_triangle )

local contacts, extouch = want_contact_triangles and {}, want_extouch_triangle and {}

local circles = {}

DoExcircle( px, py, qx, qy, rx, ry, circles, contacts, extouch, 1 )

DoExcircle( qx, qy, rx, ry, px, py, circles, contacts, extouch, 2 )

DoExcircle( rx, ry, px, py, qx, qy, circles, contacts, extouch, 3 )

return circles, contacts, extouch

end(NOTES: In that same bit of code, the stuff in comments is following the material in the section, whereas the code itself is jumping the gun... or rather using the tangent logic from the circles section... make this clear)

EXERCISES

1. Find trilinear coordinates for each excenter.

Circles all the way down (E)

By allowing the sides of the original triangle to extend indefinitely, we could also find three circles around on its outside that also happen to be tangent on each side. For that matter, another circle touches them all as well as the incircle; yet another surrounds them all.

(NOTES: Revise since we cover excircles)

We can keep going with this. The contact triangle, for instance, will have its own inscribed circle, which will introduce an infinite sequence.

As far as a circle is concerned, these centers and radii are nothing special. However, since they arise on account of a triangle, in a sense they belong to it. Such special points fall under the heading of triangle center. Many of these have interesting properties, as the circumcenter and incenter show. While literally impossible to know all of them, it is good to be aware of them.

(NOTES: Mention Apollonius circle)

Summary

Thus far, our investigations have covered triangles and circles. We have examined many of their properties, such as angles, lengths, and areas, and various facts that follow from them.

The next article will bring vectors into the fold. We will explore new ground, of course, but also build on our many discoveries thus far.